The fire that rampaged through the San Lorenzo Valley in August and September burned hotter and destroyed more acreage than anyone in these rugged, rural and breathtaking mountains can remember.

The CZU August Lightning Complex fire killed Tad Jones, a 73-year-old man who lived in the mountains above Santa Cruz. It also destroyed hundreds of homes, displacing residents, and left scores without potable water.

Now the region is bracing for more devastation, in the form of potentially deadly debris flows caused by winter storms. Taking advantage of an unusually dry November and early December, local first responders and government agencies are frantically cleaning the debris left behind by the fires, and securing the search and rescue equipment they will need for the mudslides almost sure to come.

Yet even with the looming threat, public officials and residents are confident that most residents will return and rebuild.

“If there’s one thing you need to know about the people who live in the Santa Cruz Mountains,” said Mark Stone, the area’s state assemblyman, “they are resilient.”

Federal, state and local scientists, along with other experts, all say that widespread and potentially devastating debris flows are likely to hit the region this winter.

That’s because the Santa Cruz Mountains, with their steep terrain and history of drenching storms coming off the Pacific, were burned so badly and extensively that the lattice of roots and foliage that typically holds the ground in place is gone.

“The worry is that in some places, the sides of these mountains could turn into jelly” and slough off, said Brian Collins, a civil engineer with the United States Geological Survey.

But people who’ve chosen to live in these normally damp redwood forests, not far from the Bay Area but isolated because of the rugged topography, are accustomed to the risks of mudslides, earthquakes, floods and drought. “They’re undaunted,” said Stone, a former tech industry attorney and professor at the Naval Postgraduate School.

Several years ago, a large tree fell across California Highway 17, the mountainous and treacherous high-speed corridor connecting Santa Cruz and San Jose.

“Traffic was stopped. The lanes were completely blocked,” Stone said. But before Caltrans could arrive, locals had chain-sawed the tree to bits and removed it from the road.

“They all just got out of their cars, grabbed a chain saw out of their back seat, trunk or flatbed, and got to work,” he said. “That’s just the way they do things.”

Mark Bingham, chief of Boulder Creek’s fire department, laughed when he heard the story.

“It’s true,” he said. “When I commuted over to Santa Clara, I always carried a chain saw. You never knew what would happen. But you also knew to always be prepared. Because stuff happens. It just does.”

It’s why he’s now working overtime — training local and regional firefighters and rescue workers — to prepare for a winter that he and other public officials are eyeing with trepidation.

Collins, the USGS engineer, is assisting Santa Cruz County officials and the state’s geological survey to research debris flows and measure soil saturation throughout the area.

He said that although fire-triggered debris flows are common in Southern California — like the ones that struck Montecito in 2018 — they are relatively rare in the Santa Cruz Mountains, where fires rarely burn so widely or with such intensity.

Which isn’t to say the area hasn’t experienced debris flows.

“We probably get two or three a year that close roads or cause some kind of nuisance,” Bingham said.

In 1982, a lethal debris flow struck at Love Creek, just east of Boulder Creek’s downtown. The slide was not in a burn area, but instead resulted from prolonged, torrential rains that saturated the soils and turned them to liquid.

It killed 10 people, including two children, and destroyed 30 homes. Twelve others died across Santa Cruz County.

The toll of that disaster is haunting for many, including Bingham, who was little more than a toddler at the time — but whose uncle was a first responder. It stuck in his mind this summer as he watched the fires burn along the ridges and through the neighborhoods of his town.

“I thought, ‘Winter is coming,’” he said, and he began preparing.

Bingham became chief of the fire protection district in November 2019 after a two-month transition. During his brief tenure, he has overseen the town’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, dealt with an active shooter who killed a police officer and responded to several George Floyd demonstrations and the area’s largest recent conflagration.

With no illusion that the next few months will be any easier, he’s leaning on the lessons he’s learned in the last 13. He’s also preparing his town, county responders and others for a winter of potential disaster.

Two weeks ago, his department hosted a debris flow search and rescue training seminar, with help from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and local and regional fire, search and rescue instructors.

Debris flow veterans, such as Eric Gray, a Santa Barbara fire captain who was at the scene at Montecito, and Thom Jaquysh and Tim Houweling, with California’s Task Force 3, walked attendees through their experiences and best practices.

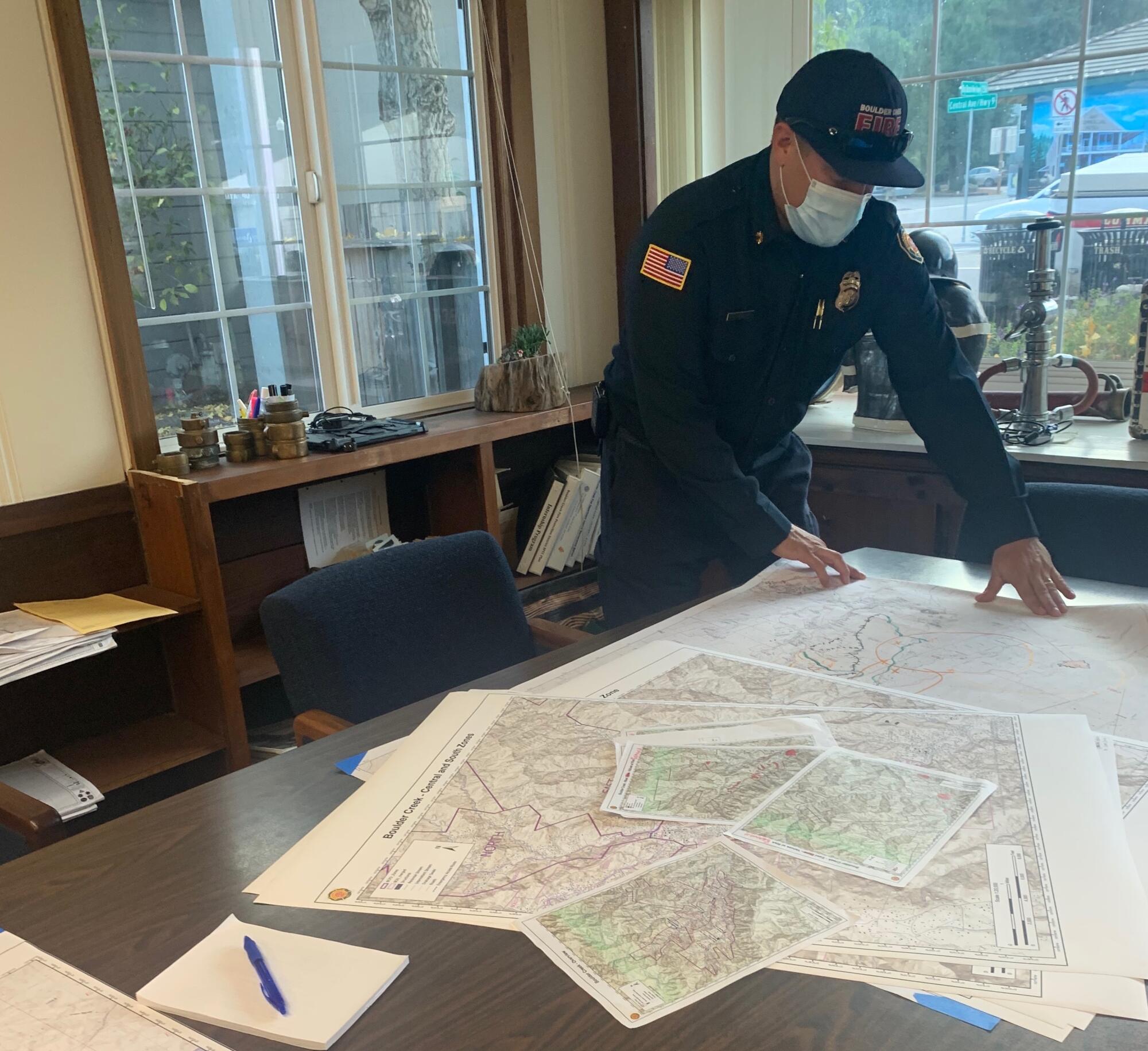

He’s also charted new maps for the area, with designated evacuation zones developed with help from the sheriff’s department and neighboring fire departments. Out-of-town first responders will have these maps, with QR codes on them, should they need to come in for search and rescue operations this winter.

“I want to make sure they know where all the access roads are, which roads are gated, how to get in, where there are bridges,” Bingham said. “I don’t want anybody getting stuck or turned around or delayed because they don’t have the information they need.”

And, with the very little money he has to work with — he’s in an unincorporated district that relies on property taxes for funding, where hundreds of houses burned this summer — he’s also trying to secure equipment. These include mud lances and dry suits that will allow his volunteers to get where they need to go, without risking their lives or ruining their firefighting equipment.

In the meantime, the county and state are working on a very aggressive timeline to get debris from the fires cleaned up, said Jason Hoppin, spokesman for Santa Cruz County.

Phase I, hazardous material removal, was completed on Dec. 1. And applications for Phase 2 — debris removal — are due on Dec. 15.

Bradley Brown, the owner of Big Basin Vineyards, said fire crews saved his winery from burning, although they couldn’t save his house.

An architectural marvel and local music venue, the stone-and-beam home was designed, in part, as a solar calendar — capturing the sun’s rays for full effect at the solstice and equinox. It is now mostly rubble and ash.

During a November visit, a reporter could see a few scorched books still sitting in the stone shelves. The roof’s terra cotta tiles, held together by wire, dangled from the few stone walls that remained, and chimed in the breeze.

He’s unsure if he’s going to rebuild the house, or if he even can. It was unique. But he’s not giving up on the winery.

“We’ve got work to do. But that’s what we do. We roll up our sleeves and get moving,” he said, adding that he spent years working the land with his own hands — chopping down trees, digging up roots, planting the vines.

Pointing toward a slump in a nearby hill — the unmistakable fingerprint of a past debris flow — he said he’s not too concerned about his grapes and the potential for landslides. He’s high up on a hill, and most of the vines and grass are still rooted, providing a structure for the soil.

But if another natural disaster should fall, he said, it’ll just be one more in a long line of them.

“You don’t live here or move here if you’re risk averse or unwilling to work hard,” he said. “You wouldn’t survive.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.